Reality Has a Surprising Amount of Detail

This article is inspired by a recent article in Taylor Pearson's newsletter

A little exercise for you:

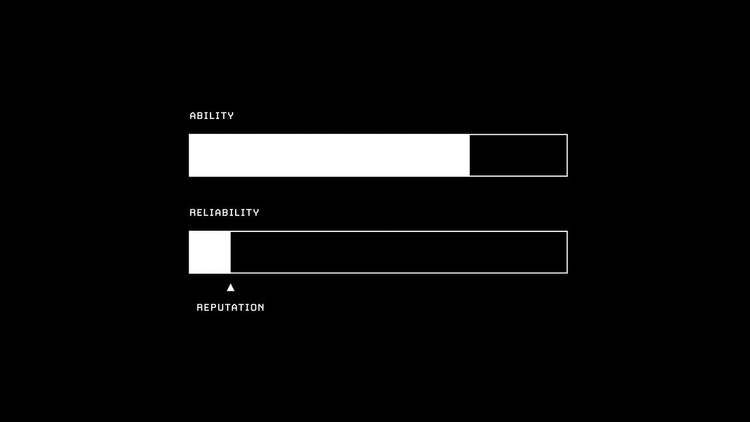

On a scale of 1 to 10, how well do you understand how a can opener works? Got a number? Good.

Now, take out a piece of paper and try to draw a diagram of a can opener. If you can’t draw well, write out an explanation, piece by piece. Seriously, take out a piece of paper and do it. (Doing it in your head doesn't count, as we will see...)

A can opener is not that complicated and you’ve probably used one hundreds, if not thousands, of times in your life.

And if you are thinking "of course I know how a can opener works" then, seriously, try to draw the diagram or write out an explanation.

After you’ve done it, re-rate your understanding on a scale of 1-10.

Spoiler alert: I and lots of other people have tried it and the initial overconfidence quickly makes way for the humble realization that our detailed understanding of everyday items is far less developed as we might think.

In a 2002 study by Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil, they observed:

"Most people feel they understand the world with far greater detail, coherence, and depth than they really do. … [They] wrongly attribute far too much fidelity and detail to their mental representations because the sparse renderings do have some efficacy and do provide a rush of insight."

This phenomenon doesn’t only apply to kitchen appliances, but basically everything everywhere.

At the population level, saying "reality has a surprising amount of detail" implies that no one understands how anything works but everyone thinks they understand how everything works.

Taylor Pearson found that the political arena is especially prone to this:

After subjects tried to explain how proposed political programs they supported would actually work, their confidence in them dropped. Subjects realized that their explanations were not very good and that they didn’t really understand the programs. This decreased their certainty that they would work. The subjects then expressed more moderate opinions and became less willing to make political donations in support of the programs.

Over the past couple of weeks we could observe this phenomenon first hand. "The Experts" outside of the scientific community (including the media) believe they are capable of predicting the effects of how specific policy decisions influence the (world) economy and society at large. Only caveat: The macro economy is 10000x more complex than a can opener and yet this same illusion of understanding persists.

So while we are all entitled to voicing our own opinion, I think it's useful to keep in mind that the actual reality of anything in our world has a surprising amount of detail when you break the systems down into its individual components. And we need to be especially careful if we are outside of our personal circle of competence (i.e. when we don't know what we don't know), to not draw (and publish) oversimplified conclusions based on superficial knowledge of the problem at hand.